Transformation through imagination – British folk and their toys Posted on

FOLK TOYS

Much has been written about folk art, popular art, naive art …. but where is the history of British folk toys? Whenever we think of folk toys we recognise those from Germany, Czechoslovakia, Mexico, Japan, Russia and India – books have been published on the folk toys from these countries. The toys are colourful, quirky, naive, but it’s hard to conjure up images of British folk toys, except those made by twentieth-century artists using the imagery of ‘folk’ such as Sam Smith, and Ron Fuller – who described himself as a village toymaker. There are other modern artist/designers whose work is informed by folk art traditions, but it’s not ‘folk art’ as we understand it. The artist Peter Blake is a hoarder of popular art, and has a celebrated collection of toys which he often incorporates into his work.

Patrick Murray, the idiosyncratic creator of the Edinburgh Museum of Childhood says in the introduction to his book ‘Toys’ (1968), “…. with the exception of balls, hoops, dolls, animals …. there are no real traditional toys.”

None of the books on British Folk Art appear to mention toys, apart from the odd example made in bone by a Napoleonic prisoner of war. Even the vast Marx-Lambert collection of popular art at Compton Verney only has a small number of British toys – a rocking horse, a kaleidoscope, and a doll possibly made by Enid Marx herself. The traditional Folk Toy is elusive. Punch and Judy and other puppets are usually designated as popular art rather than toys.

The European countries that produced the folk toys in the nineteenth century consisted mainly of poor ‘peasant’ communities turning out a wide variety of toys in wood or papier mache to be sold in the big towns. Britain was the first to become industrialised, thus pushing the vernacular traditions of the countryside out of sight. The Victorian city poor would make objects from materials easily found such as coal, straw, bone, wood, or cloth; the ones that have survived have been collected as folk art, but any individual toys – dolls, wooden animals – cannot be identified as inherently British. It seems we don’t have our own folk toys, although on the other hand, we enjoy collecting the cheap ephemeral ‘popular art’ toys of the twentieth century which have the quirky, and bright humour of nineteenth century folk toys, such as fairground souvenirs, tin toys, plastic space guns, the toy theatre and other objects that rely on amusing bold graphics.

Kenneth and Marguerite Fawdry who created Pollocks Toy Museum in London, took their car on holiday trips from the 1950s every year into Eastern Europe, scouring markets for local children’s toys. Their finds can still be seen in the museum in London. They followed in the footsteps of Paul and Marjorie Abbatt who did similar trips in the 1930s.

Many artists in the past collected children’s toys, and bequeathed them to museums. Alexander Girard the architect and designer, amassed an enormous collection of mostly Mexican traditional items, which can be seen in the International Museum of Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

British Folk Toys

Edward Lovett (1852-1933) was a folklorist who spent his spare time collecting, writing, and lecturing on folk-lore and superstition. He became an authority on ethnographic dolls, and formed an interest in home-made ‘emergent’ or ‘slum’ toys created by poor children. He built up his collection by exchanging toys he found on his travels for new ones he’d bought with him especially to barter.

Lovett frequently visited London’s poorer districts, large provincial towns, as well as small villages to collect playthings made from a wide variety of discarded or household objects – rags, bones, wooden spoons, brushes, pegs, shoes, fir cones, shells, acorns, dried seaweed. In the Museum of Childhood in Edinburgh, they have at least seven loofah dolls, one made from a clothes whisk, one from a clog, and one shoe doll where the heel forms the face and stick limbs are covered with fabric. The Museum has many rag dolls made from stuffed cloth with painted features. One is described as being made by a four-year old miner’s child (1913), that has a blue and white headscarf decorated with a feather. A rag doll (c. 1910) with a paper body covered with white cotton, has no head or limbs. Many of the bone dolls are wrapped in cloth without any features.

Some of these folk toys are in various museums including the Museum of Childhood in Edinburgh, and the Horniman Museum in London.

The British Museum of Folklore has documented the British folk tradition of Morris dancing by asking practitioners to make dolls with their costumes. It has collected 273 Morris Folk contemporary dolls and exhibits them around Britain.

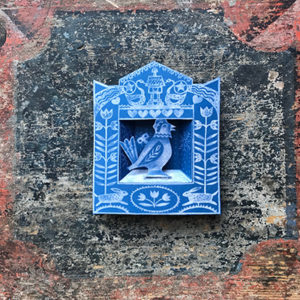

To celebrate our season on Folk Toys we have created a Harlequinade Folder ‘From the Forest to the Fantastical’ which contains a limited edition ‘Folk Art’ miniature theatre to cut out and make by Clive Hicks-Jenkins